A New Way to Tune X-ray Laser Pulses

A new system at SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory's X-ray laser narrows a rainbow spectrum of X-ray colors to a more intense band of light, creating a much more powerful way to view fine details in samples at the scale of atoms and molecules.

By Glenn Roberts Jr.

A new system at SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory's X-ray laser narrows a rainbow spectrum of X-ray colors to a more intense band of light, creating a much more powerful way to view fine details in samples at the scale of atoms and molecules.

“It’s like going from regular television to HDTV,” said Norbert Holtkamp, SLAC deputy director and leader of the lab's Accelerator Directorate.

Designed and installed at SLAC's Linac Coherent Light Source (LCLS) in collaboration with Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory and Switzerland’s Paul Scherrer Institute, it is the world’s first “self-seeding” system for enhancing lower-energy or "soft" X-rays.

Scientists had to overcome a series of engineering challenges to build it, and it is already drawing international interest for its potential use at other X-ray free-electron lasers.

"Because this system delivers more intense soft X-ray light at the precise energy we want for experiments, we can make measurements at a far faster rate," said Bill Schlotter, an LCLS staff scientist. "It will open new possibilities, from exploring exotic materials and biological and chemical samples in greater detail to improving our view of the behavior of atoms and molecules.”

Cutting Through the Noise

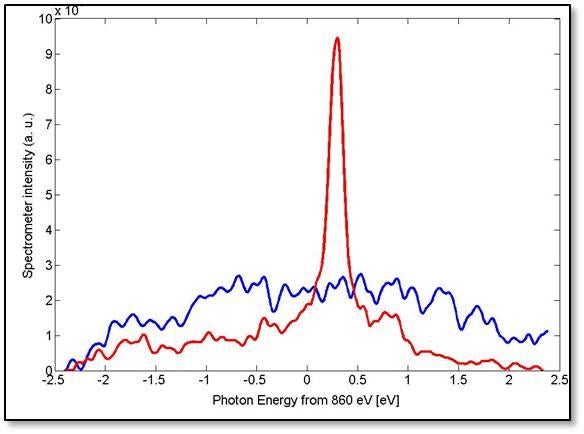

LCLS’s laser pulses vary in intensity and color, and this randomness or “noise,” like fuzzy reception on a TV, sometimes complicates experiments and data analysis. Self-seeding cuts through this noise by providing a stronger and more consistent intensity peak within each laser pulse.

"We're taking something that's in a range of colors and trying to select a single color and pack as much power in as we can," said Daniel Ratner, an associate staff scientist at SLAC and lead scientist on the project. "We're going from the randomness of a typical pulse to a nice, clean, narrow profile that is well-understood.”

Scientists had installed another self-seeding system at LCLS in 2012 for higher-energy "hard" X-rays. It has been put to use in studies of matter under extreme temperatures and pressures, the structure of biological molecules and electron motions in materials, for example.

Extending self-seeding to soft X-rays was a logical next step. LCLS scientists Yiping Feng, Daniele Cocco and others designed a compact X-ray optics system that was key to the success of the project, which was led by SLAC's Jerry Hastings and Zhirong Huang.

The team achieved self-seeding with soft X-rays in December, and conducted follow-up tests in January and February. They are working to improve the system and to make it available to visiting scientists.

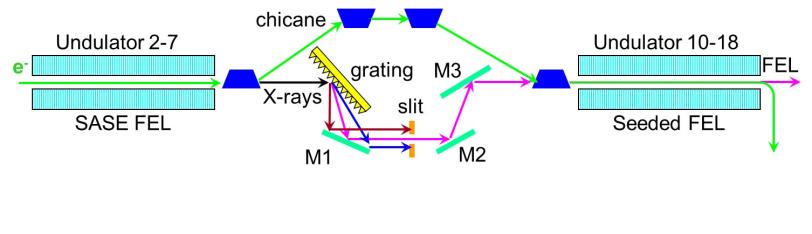

LCLS X-ray pulses are powered by an electron beam from SLAC's linear accelerator. The electrons wiggle through a series of powerful magnets, called undulators. This forces them to emit X-ray light, and that light grows in intensity as it moves through the undulator chain.

The new system, installed about a quarter of the way down the undulator chain, diverts a narrow, purified slice of the X-ray laser light and briefly and precisely overlaps it with the beam of electrons traveling through the undulators. This produces a “seed” – a spike of high-intensity light in a single color – that is amplified as the X-ray pulses move through the remaining undulators toward LCLS experimental stations.

Engineering Challenge

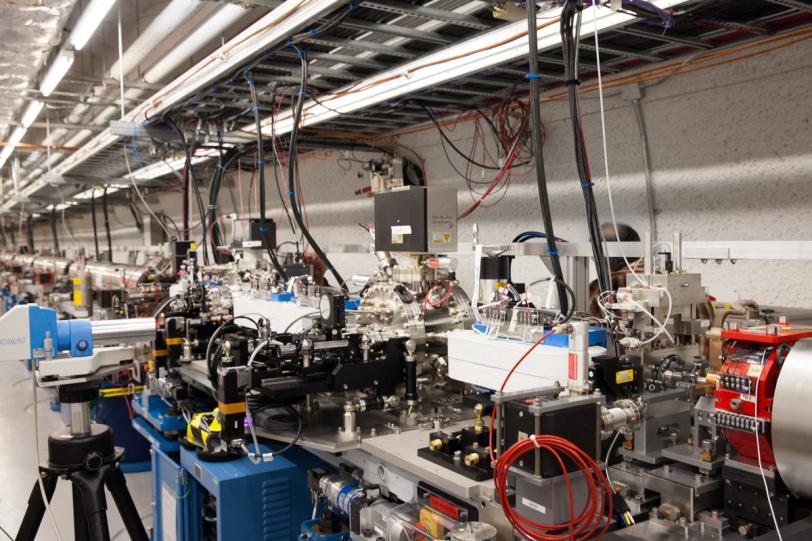

"A big technical challenge was to fit everything in one 13-foot-long undulator section," including a complex network of cabling, optics, magnets and mechanical systems, said SLAC's Paul Montanez, project manager and lead engineer for the system. "A tremendous number of people pulled this project together, from administrative, technical and professional staff to scientists."

The Berkeley Lab team designed and built the hardware that diverts and refines the X-ray light, as well as mechanical systems that align the X-rays and electrons, adjust the X-ray energy and retract components out of the path of X-rays when not in use. The Paul Scherrer team designed and built the optical equipment for the system. SLAC was responsible for integrating the components and building the controls that automate the system.

"This project was pretty challenging in that we were designing and developing and installing this equipment in an operating facility, with little time for the actual installation," said Ken Chow, the lead engineer for the Berkeley Lab effort. He noted that the project required many custom parts, such as a movable mirror that must rotate with incredible precision – "It's like taking a meter stick and moving one end one-half millionth of a meter," he said.

Next Steps

SLAC scientists are hoping to use the seeding system, coupled with an intricate tuning of the magnets in the undulators, to produce even higher-intensity pulses for the next generation of X-ray lasers.

Already, collaborators from the Paul Scherrer Institute are considering a similar self-seeding system for a planned soft X-ray laser in Switzerland, and there has been great interest in such a system for other X-ray laser projects in the works.

"We would like to learn and profit from this for our own project, the SwissFEL," said Uwe Flechsig, who led the Paul Scherrer team that was responsible for delivering the system's optics.

SLAC is a multi-program laboratory exploring frontier questions in photon science, astrophysics, particle physics and accelerator research. Located in Menlo Park, California, SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science. To learn more, please visit www.slac.stanford.edu.

SLAC’s LCLS is the world’s most powerful X-ray free-electron laser. A DOE Office of Science national user facility, its highly focused beam shines a billion times brighter than previous X-ray sources to shed light on fundamental processes of chemistry, materials and energy science, technology and life itself. For more information, visit lcls.slac.stanford.edu.

DOE’s Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit science.energy.gov.